The Civil War Siege of Petersburg from June 1864 to April 1865 is the historical event that has made the city internationally known, but relatively few Virginians know about the Revolutionary War Battle of Petersburg. Virginia was the scene of some small battles soon after the war began, and some British forces operated in and around Virginia in 1779 and 1780. In 1781, however, Virginians felt the full fury of the war.

The Civil War Siege of Petersburg from June 1864 to April 1865 is the historical event that has made the city internationally known, but relatively few Virginians know about the Revolutionary War Battle of Petersburg. Virginia was the scene of some small battles soon after the war began, and some British forces operated in and around Virginia in 1779 and 1780. In 1781, however, Virginians felt the full fury of the war.

Petersburg was designated as a chief magazine for storing arms and ammunition in Virginia in 1775, and in March 1780 General George Washington designated Petersburg as one of four Continental Army supply depots in the state. After the American defeat at Camden, South Carolina, in 1780, Washington sent Major General Nathanael Greene to command the Southern Army. Concurrently, Washington assigned Major General Friedrich Wilhelm Augustus von Steuben to Greene, who tasked him with organizing supplies and defenses in Virginia. Von Steuben had two forces in the state, one under Brigadier General Thomas Nelson Jr. north of the James River and one under Brigadier General John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg south of the river.

British Major General William Phillips arrived in Portsmouth, Virginia, in March 1781 with approximately 3,000 soldiers and he assumed command of British forces in Virginia from Brigadier General Benedict Arnold. Ironically, Arnold had been the American most responsible for the British defeat at Saratoga, New York, in 1777, which led to Phillips’s surrender and three-year imprisonment. Phillips’s mission was to sever the American line of communications through Virginia that supported Greene’s army. This would assist Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis’s British army in North Carolina. The route now followed by U.S. Highway 1 was the major line of communications between the northern and southern states through Virginia. The stage was being set for Petersburg to become the focus of the Revolutionary War in April and May of 1781, as British Generals Phillips and Arnold and American Generals von Steuben, Muhlenberg, the Marquis de Lafayette, and Anthony Wayne and their soldiers fought in and around the city.

Petersburg was a British objective because it was a water and land communications hub, because it was a major tobacco trading center (which was the reason for its wealth) and, most importantly, because it was a supply point for Greene’s army in the South. It may also have been the largest settlement in Virginia; in 1782, Petersburg’s population was 2828, which was almost three times that of Richmond’s 1031 inhabitants. Phillips’s plan was to send gunboats down the Appomattox River while marching overland from City Point (present-day Hopewell) west to Petersburg and then attack the American forces defending the city. Phillips’s military objectives were to capture American supplies, cut the American armies’ communications with General Greene’s Southern Army, and link up with General Cornwallis’s troops marching north from Wilmington, North Carolina. Phillips’s army moved upriver from Portsmouth on April 18. Concurrently, Muhlenberg’s Virginia force, which had contained Phillips at Portsmouth, marched west along the south side of the James River. The British landed at City Point, on April 24. The Americans entered Petersburg on the same day.

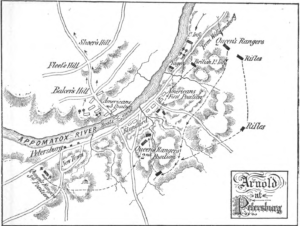

The American commanders, von Steuben and Muhlenberg, knew that their outnumbered force of 1,200 militiamen would not defeat Phillips’s regulars, but they also knew that they had to make a stand at Petersburg and then retreat across the Appomattox River, in good order if at all possible. The American militiamen were not regular, Continental Army soldiers but were armed civilians in local militia units. They did not possess the level of training and discipline of Continental Army soldiers, and certainly they were not as proficient as Cornwallis’s British Army soldiers. Of von Steuben’s five regiments, two were positioned at Poor’s Creek (near the current location of Virginia Linen). Their line ran from a wharf on the Appomattox River south to the foot of Well’s Hill, where Blandford Church still stands after approximately 279 years. Another two regiments were placed on the west side of Lieutenant’s Run along present-day Madison Street, from the river south to the Bollingbrook estate on East Hill. Von Steuben placed the fifth regiment north of the Appomattox River to cover the withdrawal from Petersburg and to guard the Pocahontas Bridge. This bridge was the only one over the Appomattox River for about 20 miles, and it was 12 to 15 feet wide and 35 feet long. Von Steuben sited his two artillery pieces on the heights north of Petersburg (in present-day Colonial Heights), where they would be in range of the British forces attacking south of the river.

On the morning of April 25, Phillips began his water and ground attack on Petersburg. He sent 11 gunboats carrying infantrymen, supplies, and possibly a small cannon down the Appomattox River. The bulk of his army then began the 12-mile-march to Petersburg on River Road (now Puddledock Road) to a road junction (now Route 36). His force then headed west for a short distance to Petersburg. At approximately 11 a.m., Phillips’ gunboats were sighted by an American infantry company at the Point of Rocks on the north shore of the Appomattox River. About an hour later, American Captain Rice saw the gunboats from his position at the Brick House (a circa 1675 house still standing at Conjurer’s Neck in Colonial Heights).

Meanwhile, the British regulars attacked von Steuben’s first line of defense along Poor’s Creek. The militiamen conducted a spirited defense and drove the British back. After about 30 minutes, the British brought up two 3-pounder and two 6-pounder artillery pieces. At this point, von Steuben ordered the two regiments along this line to fall back and join the second line west of Lieutenant’s Run. When Phillips saw that the American right flank ended at the base of Well’s Hill, he ordered Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe to outflank the Americans with the Queen’s Rangers and a battalion of light infantry. Simcoe’s force was able to get around the American right flank, but it did not arrive in Petersburg in time to cut off the American retreat across the Appomattox River.

The second American line then consisted of two regiments that had not seen action, plus the two regiments that had retired from the first line of defense. As Phillips’s army attacked the four regiments, it was repelled several times. This second American line held the British back for about an hour, and von Steuben ordered the withdrawal across the river. The Americans fought a delaying action, with considerable hand-to-hand fighting south of the bridge. Von Steuben’s force was able to cross the Pocahontas Bridge, take up the bridge’s planks to prevent the British from pursuing, and withdraw up the hill north of the river. The retreat began in an orderly fashion until British artillery ranged the road on which the militia was retreating, and then it became a rout.

By Revolutionary War standards, this fight was more than a skirmish; it was a battle with 3500 soldiers engaged for almost three hours. The number of casualties in this battle varies, but American losses were about 150 casualties, while the British suffered approximately 20 casualties. On the day after the battle, Phillips told the city leaders that he would burn only tobacco if the citizens moved the tobacco out of the warehouses and into the streets. The British burned the tobacco removed from three of the warehouses. However, the Cedar Point Warehouse was burned along with its tobacco, allegedly because a British soldier did not receive the order to spare the warehouse.

Phillips returned to Petersburg on May 9. Major General Marquis de Lafayette sent two artillery pieces to bombard Petersburg on May 10 while Phillips lay dying at the Bolling residence at East Hill. He died on May 13, possibly of typhoid fever. Arnold ordered that his body be buried at Blandford Church that night in an unmarked grave.

In a letter to John Bland providing his account of the battle on May 16, 1781, Colonel John Banister stated that this “little affair shows plainly the militia will fight.” The Battle of Petersburg, while not an American victory, became one of the opening clashes in the campaign that would decide the war. Less than three months later, Cornwallis moved his entire army south of the James River after Lafayette shadowed, and on occasion, contested his movements. Within six months of the Battle of Petersburg, Cornwallis surrendered the troops who had fought at Petersburg and about 4,000 additional British and Hessian soldiers to the combined American and French armies. The Duc de Lauzun’s Legion, a French unit of infantry and cavalry, accepted the British surrender of Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton’s men at Gloucester Point on October 19. Ironically, on June 17, 1782, the infantrymen in this 600-man unit encamped where Phillips was interred, at Blandford Church.

The City of Petersburg remembers its role in the Revolutionary War with a free re-enactment of the Battle of Petersburg at historic Battersea on the third weekend in April each year. This National Historic Register-listed property was built in 1768 by the aforementioned Colonel John Banister, who signed the Articles of Confederation and was also elected the first mayor of Petersburg in 1784. British troops occupied his house and estate at least twice in 1781. The 2014 re-enactment will be on April 19 and 20. Bring the entire family!