Petersburg, Virginia, is known first and foremost for being on the receiving end of the longest siege in American history. The siege began on June 15, 1864, with the Union Army’s attack on Confederate earthworks east of the city, and it ended with the withdrawal of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia from Petersburg and Richmond by early morning on April 3, 1865. As the term siege implies, the citizens of Petersburg endured daily Union artillery bombardment and scarce food and other necessities for 292 days, just as the Confederate soldiers defending the city had to. When Confederate General Robert E. Lee ordered the evacuation of his soldiers from Petersburg and Richmond on April 2, 1865, the Army of Northern Virginia survived a mere seven days before surrendering to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

Petersburg, Virginia, is known first and foremost for being on the receiving end of the longest siege in American history. The siege began on June 15, 1864, with the Union Army’s attack on Confederate earthworks east of the city, and it ended with the withdrawal of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia from Petersburg and Richmond by early morning on April 3, 1865. As the term siege implies, the citizens of Petersburg endured daily Union artillery bombardment and scarce food and other necessities for 292 days, just as the Confederate soldiers defending the city had to. When Confederate General Robert E. Lee ordered the evacuation of his soldiers from Petersburg and Richmond on April 2, 1865, the Army of Northern Virginia survived a mere seven days before surrendering to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

Petersburg was the seventh largest city in the Confederate States of America, and the 49th largest in the United States. It was largely unaffected by Major General George B. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign from early May to early July 1862, except for the large numbers of soldiers from Petersburg who were killed or wounded while serving in the 12th Virginia Infantry Regiment and other units. Petersburg was not only an important Confederate manufacturing center, but five railroads converged on the city. Early in the war the city was recognized as a major transportation hub through which many of the supplies for the Army of Northern Virginia moved.

In 1862, Captain Charles H. Dimmock arrived from Richmond to build earthen defenses around Petersburg. When they were completed the following year, the defenses, which became known as the Dimmock Line, included 55 batteries connected by lines of earthworks. They began east of the city on the Appomattox River, extended around the south of the city, and ended on the Appomattox River west of the city.

The Confederate officer responsible for the defense of Petersburg in 1864 was General Pierre G.T. Beauregard. After his successful defense of Charleston, South Carolina, in April 1863, Beauregard expected to command one of the two largest Confederate armies. Instead, on April 23, 1864, President Jefferson Davis assigned him to replace Major General George E. Pickett as the Commander of the Department of North Carolina and Southern Virginia. This department included Virginia south of the James River.

Meanwhile, back in Washington, Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to lieutenant general on March 9, 1864. Three days later, President Abraham Lincoln named him the General in Chief of the Armies of the United States. Grant’s strategy in 1864 was to put pressure on many points at the same time so that the Confederates would not be able to mass their forces. He therefore directed that six Union armies attack in early May, including Major General Benjamin F. Butler’s Army of the James at Bermuda Hundred (in present-day Chesterfield County, across the Appomattox River from Hopewell) and Major General George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac in the vicinity of Culpeper.

On May 4, 1864, Meade’s army moved south and crossed the Rapidan River into a heavily forested area known as the Wilderness. For the next two days, the Armies of the Potomac and Northern Virginia fought a vicious battle in this dense undergrowth. Grant decided to move southeast around Lee’s right flank, and over the next five weeks Union attacks at the Battles of Spotsylvania Court House, North Anna, and Cold Harbor inexorably pushed Lee south to the outskirts of Richmond. At Cold Harbor on June 3, Grant attacked well- entrenched Confederates and was repulsed with heavy losses. On the following day, Grant decided to strike at Lee by crossing the James River. He intended to sever the supply lines into Petersburg that were supporting Lee’s army and to either starve him out or force him to fight in the open.

At this time, Petersburg had yet to feel the hard hand of war. This was about to change drastically. A former Virginia governor, Brigadier General Henry A. Wise, was in charge of the defense of Petersburg under General Beauregard. Under Wise’s command were only two small veteran units, a light artillery battery, and two battalions of Petersburg militia, for a total of approximately 1,200 men. The war came to Petersburg with a battle on June 9. Major Fletcher H. Archer’s “old men and young boys” fought bravely and delayed Brigadier General Augustus V. Kautz’s Federal cavalry brigade that attacked along the Jerusalem Plank Road (now South Crater Road). Out of Archer’s 125 men, 75 became casualties, including 15 killed in action. Among the dead were William C. Banister, a 61-year old banker in the Exchange Bank, and George B. Jones, a well-known druggist. Both men were the father of six children. On June 12, Wise wrote in his Special Orders No. 11, “Petersburg is to be and shall be defended on her outer walls, on her inner lines, at her corporation bounds, on every street, and around every temple of God and altar of man, in her every heart, until the blood of that heart is spilt.” Three days later, the 9 ½-month siege of Petersburg began.

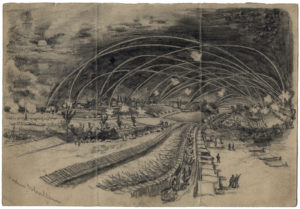

Early in June, Lee told Major General Jubal Early, “We must destroy this Army of Grant’s before he gets to the James River. If he gets there it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time.” Beginning on June 12, Grant evacuated 100,000 soldiers along a 10-mile front east of Richmond, marched approximately 50 miles through swampy terrain, and crossed the James River to attack Petersburg. Most of the Union forces were on the march on the moonlit night of June 12-13, and many soldiers recalled the immense dust from the thousands of men on the move. On the morning of June 13, Lee did not know the location of the Army of the Potomac nor the intentions of its commander. Before noon on June 14, the Army of the Potomac began crossing the James River in a collection of boats from Willcox’s Landing on the north bank to Windmill Point (Flowerdew Hundred Plantation) on the south bank. That afternoon, 450 Union engineers constructed a 2,100-foot pontoon bridge across the James River in a mere nine hours. Just after midnight on June 15, this bridge was ready for traffic.

Since Lee still did not realize the ongoing movement of much of Grant’s army south of the James, Beauregard had only 2,200 troops in the lines defending Petersburg. Early on the morning of June 15, the siege of Petersburg began as Kautz’s cavalry brigade stumbled upon Confederate soldiers at Baylor’s Farm, a few miles northeast of Petersburg (approximately where the I-295 overpass crosses Route 36 in Hopewell). By noon on June 15, Major General William F. “Baldy” Smith and his 16,000 soldiers from the Army of the James were attacking Petersburg. At about 6:00 pm, Smith’s XVIII Corps launched an attack on the Dimmock Line against the heavily outnumbered defenders. In three hours, Smith’s soldiers, including several regiments of United States Colored Troops, captured 11 of the 55 batteries defending Petersburg and about two miles of Confederate earthworks. Later that night, Beauregard patched together another line of defense on the high ground west of Harrison’s Creek. Regarding that night, Beauregard later wrote, “Petersburg at that hour was clearly at the mercy of the Federal commander, who had all but captured it, and only failed of final success because he could not realize the fact of the unparalleled disparity between the two contending forces.”

The Federals continued their attacks on June 16, and by the 17th Lee recognized that the bulk of Union forces were south of the river. He began moving the rest of his army south into Petersburg, personally entering the city just before noon that day. On June 18, about 50,000 Confederates confronted 90,000 Federals east of Petersburg. In one of the last assaults on Confederate lines that afternoon, the 1st Maine Heavy Artillery attacked near the Hare House with about 900 soldiers. Within 30 minutes, this regiment suffered 612 casualties, which was the largest loss of any regiment in one fight during the entire Civil War.

Just after midnight on June 18, Beauregard ordered a withdrawal to construct a new defensive line about a mile closer to Petersburg. Unfortunately, the Union forces would then be close enough to fire artillery into the city. The four days of attacks on the eastern part of the Dimmock Line from June 15-18 cost the Union about 10,000 casualties and the Confederates about 4,000 soldiers. What would become the longest siege in American history had begun.