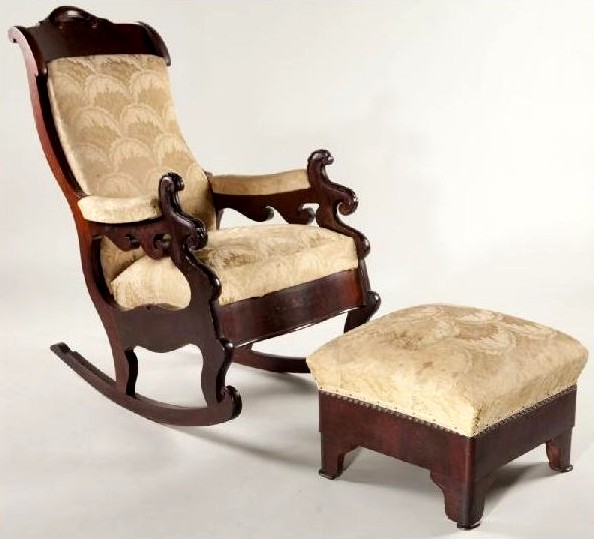

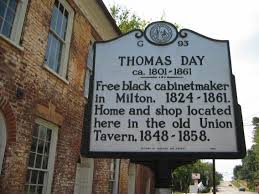

One of the antebellum South’s most successful craftsman, Thomas Day, was born in Dinwiddie County, Virginia, in 1801, to free parents of African descent. He apprenticed as an early age to his father, who was a woodworker in Petersburg. In the early 1820s, he moved with his family to Milton, North Carolina, just south of Danville, Virginia. Day not only created and designed his own distinctive style of formal furniture and interior architecture for prominent homes and public buildings for three decades, he became a founding member of the modern Southern furniture industry.

At a time when furniture and millwork was produced by individual craftsmen, Day introduced a methodology of industrial production utilizing steam powered tools in which some employees produced separate elements of a final product assembled by other artisans. At the height of his career in 1850 he employed as many as 20 workers, both white and black, in his shop, which created one-sixth of the total furniture output that year in North Carolina. His entrepreneurship, excellence of design and more efficient construction techniques boosted production, lowered costs and built him a substantial fortune.

In a recent article in the Richmond-Times Dispatch, Howard Baugh, son of Petersburg native and Tuskegee Airman Howard L. Baugh said, “Black history is American history and we have Black History Month because black history was not recorded.”

Fortunately for those of us who love history, especially American history, the story of Dinwiddie County native Thomas Day is somewhat of an exception. The life and work of this extraordinary individual is documented in a number of ways, much of it tied to his craft. A talented cabinetmaker, Day enjoyed freedom, economic success, and respect in the Antebellum South of the 1820s through 1860. For a black person during that time, his experience is almost without parallel. He holds an important and unique place in the annals of American architectural history. This is what is known about his life:

• 1801 – Thomas Day is born in Dinwiddie County, Virginia to father John Day, Sr., a cabinetmaker (furniture maker) in Petersburg

• 1820s – Now grown and skilled in the furniture-making trade himself, Day moves to Milton, North Carolina, to develop his own business. He employs white apprentices as well as free black and mulatto laborers. He also eventually owns slaves.

• 1830 – The North Carolina General Assembly approves a petition to allow Day’s bride, Aquilla Wilson, a free black from Virginia, to join her husband in North Carolina.

• 1847 – Day wins a contract with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to create pieces for the Philanthropic and Dialectic Societies.

• 1850 – Day’s enterprise becomes the largest furniture-making shop in North Carolina.

• 1855 – David S. Reid, who had served as Governor of North Carolina from 1843-1847, commissions Day to build furniture for his home.

• 1856 – Day wins an award and gets an “award premium” at the NC State Fair for a mahogany wardrobe he made.

• 1861 – Day dies in Milton, North Carolina

• 1936 – A Works Progress Administration (WPA) researcher, Mabel Moses, documents architectural elements in Southside Virginia created by Thomas Day.

• 1997 – Marilyn S. and James R. Melchor pen an article about Thomas Day and Houses in Halifax County for The Chesopiean, A Journal of North American Archaeology, a publication of the Institute for Human History, Gloucester, Virginia.

Today, you can visit Thomas Day’s workshop and home in Milton, North Carolina which is just below Danville, Virginia.

There is also a permanent Thomas Day exhibit in the North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh, NC.

Past exhibitions of Thomas Day architecture and decorative arts have included:

Behind the Veneer: Thomas Day, Master Cabinetmaker, North Carolina Museum of History

Thomas Day: Master Craftsman and Free Man of Color, The Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.